Indie music matters because it refuses to behave.

It doesn’t wait for permission, doesn’t ask what’s trending, doesn’t consult a branding deck before plugging in a guitar. It thrives in basements, on Bandcamp pages uploaded at 2 a.m., in college radio booths where the coffee is burnt and the signal barely clears the county line. It exists because someone, somewhere, had to get that sound out of their body.

If that sounds romantic, good. Romance is part of it. But indie music isn’t just a vibe. It’s an ecosystem, a stubborn alternative to the consolidated machinery of the global recording industry – a machinery dominated by conglomerates where quarterly returns can shape artistic decisions. Indie music, by contrast, has historically been defined less by genre than by structure: independent labels, self-released records, do-it-yourself touring circuits.

And that structural difference matters.

The term “indie” first cohered around labels such as Sub Pop and Dischord Records in the 1980s – scrappy operations that documented scenes rather than manufacturing them. Sub Pop helped export the Pacific Northwest’s snarling weirdos to the wider world, while Dischord Records, co-founded by Ian MacKaye, built an ethical framework around fair pricing and all-ages shows. These labels weren’t just distribution companies; they were community engines.

Indie music matters because it creates spaces where scenes can incubate without being immediately strip-mined for content.

Take Athens in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The town wasn’t a music capital. It was a college town with cheap rent and a handful of clubs. But out of that environment came bands like R.E.M. and The B-52’s – artists who began outside the mainstream industry’s glare. Their early records sounded like dispatches from a parallel America: jangling, strange, deeply regional. Before they were platinum, they were local.

That trajectory – from local to global without entirely shedding the local – is one of indie’s great gifts. It insists that geography, community and idiosyncrasy matter. It resists the flattening effect of algorithmic sameness.

Now, you could argue that in the age of streaming platforms, everything is “indie” and nothing is. After all, an artist can upload a track to Spotify from their bedroom and technically bypass a label. But independence is not just about distribution; it’s about control. Who owns the masters? Who decides the release schedule? Who determines whether a seven-minute feedback freakout makes the cut?

When artists retain creative and financial agency, they can take risks that a major-label A&R department might flag as commercially dubious. And risk is the lifeblood of cultural innovation.

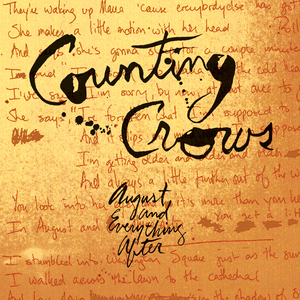

Consider how many now-canonical bands began as indie outsiders. Sonic Youth turned dissonance into architecture, building cathedrals out of alternate tunings. The Replacements wrote songs that felt like barroom confessions shouted through a broken P.A. These groups were messy, imperfect, and gloriously human. Early R.E.M. showed that you could love where you come from and need to desperately leave it. They were not optimized. That was the point.

Indie music matters because it documents emotional realities that don’t always fit radio formats. Heartbreak that’s awkward rather than cinematic. Political anger that’s granular and local rather than slogan-ready. Joy that’s weird and private.

It also matters economically. Independent venues, record stores and labels form part of a broader cultural infrastructure. A club show supports bartenders and sound engineers. A small pressing plant keeps manufacturing skills alive. When fans buy directly from artists – on tour or through platforms like Bandcamp – a greater share of revenue stays within that ecosystem.

There is, too, a pedagogical dimension. For young musicians, indie scenes function as informal schools. You learn how to book shows, how to design a flyer, how to record on a shoestring budget. You learn that art is labor and collaboration. You learn that community is not a marketing demographic but a network of actual people who will help you load gear at midnight.

And yes, indie music is prone to mythologizing itself. It can lapse into gatekeeping, fetishize obscurity or confuse lo-fi aesthetics with moral virtue. Independence does not automatically equal integrity. But the aspiration toward autonomy – toward making something because you need to, not because a focus group requested it – remains vital.

In an era of cultural consolidation and algorithmic curation, indie music represents friction. It interrupts the seamless scroll with something jagged, something that doesn’t immediately resolve. It asks listeners to lean in rather than passively consume.

That friction can be uncomfortable. It can also be transformative.

Because at its best, indie music reminds us that culture is not only something delivered to us by corporations. It is something we make together in garages, in community centers, in cramped apartments with egg cartons taped to the walls. It is sustained by volunteers at college radio stations, by promoters who take a financial gamble on an unknown band, by fans who show up on a Tuesday night.

Indie music matters because it proves that art does not have to begin with scale. It can begin with urgency. With a riff that won’t let you sleep. With a lyric scribbled on a receipt. With a handful of friends who believe that their small-town noise deserves to exist.

And once it exists, it changes the air.