If rock and roll has gravity, it’s the kind that pulls you sideways — toward the basement show, the overdriven amp, the song that sounds like it was recorded in a kitchen but somehow rearranges your emotional furniture. And for twenty years, Dayton/Columbus, Ohio’s Smug Brothers have been quietly defying that gravity by embracing it. Their forthcoming 20-year retrospective, Gravity Is Just A Way To Fall (out May 15, 2026), isn’t a victory lap so much as a beautifully scuffed scrapbook — a reminder that some of the best American guitar music of the last two decades has been hiding in plain sight.

To understand Smug Brothers, you have to start in Dayton and then take a drive to Columbus, Ohio — that stubbornly fertile patch of Midwest soil that has produced more sharp, strange guitar bands than the coasts would like to admit. Think Guided by Voices, think Times New Viking, think Cloud Nothings, think Heartless Bastards. Bands that made imperfection a matter of principle. Beautiful chaos. Bands that treated melody like contraband — something to be smuggled past the gatekeepers of taste.

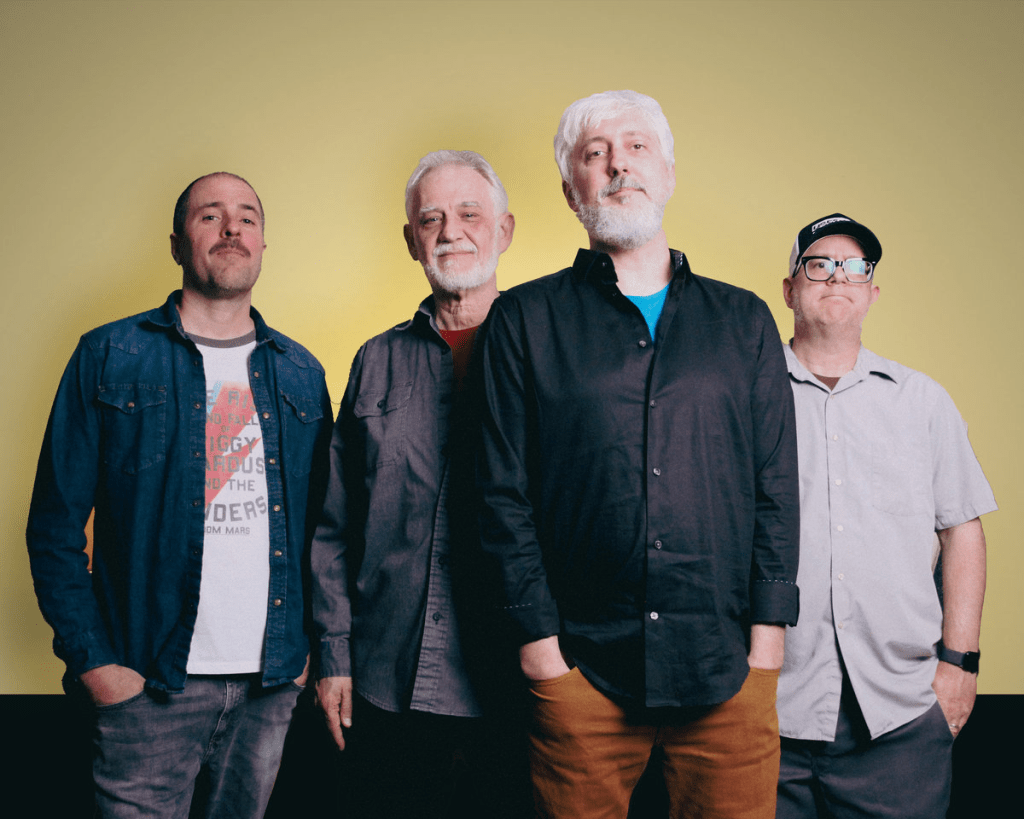

Smug Brothers fit that lineage, but they also complicate it. What began in the mid-2000s as a scrappy recording project between singer/guitarist Kyle Melton and Darryl Robbins (of Motel Beds) hardened into something deeper and more resilient when legendary drummer Don Thrasher — yes, that Don Thrasher from Guided by Voices and Swearing at Motorists — joined the fold. Since 2009, Melton and Thrasher have formed the core of a band that feels less like a stable lineup and more like an ongoing conversation over music. Over the years, that dialogue has included a rotating cast — Marc Betts, Brian Baker, Shaine Sullivan, Larry Evans, Scott Tribble, Kyle Sowash, Ryan Shaffer — all contributing to a catalog that’s as collector-friendly as it is emotionally direct. Each player adding something distinctive to the records they worked on.

But here’s the beautiful irony: you don’t need to track down the cassettes, the limited LPs, or the out-of-print CDs. Gravity Is Just A Way To Fall does the curatorial work for you. Several tracks have been remastered; some have never appeared on vinyl; a few have never existed in any physical format at all. After twenty years, the band decided to “summarize the work up to this point.” That word — summarize — sounds almost academic. What they’ve actually done is distill the fever.

And what a fever it is.

Smug Brothers have always specialized in the kind of riff-driven indie pop that feels both handmade and cosmically aligned. The early lo-fi recordings hinted at greatness — fuzzed-out guitars, melodies that ducked and weaved, drums that sounded like they were daring the tape machine to keep up. But even in those rough cuts, you could hear the bones: a Beatlesque instinct for earworms, an affection for left turns, a refusal to sand down the serrated edges.

Over time, Melton’s recording finesse sharpened. He recorded and mixed much of this retrospective himself, with key collaborations from Darryl Robbins and Micah Carli. Everything was mastered by Carl Saff, whose touch has become something of a seal of quality in indie circles. The result is a set of songs that feel alive rather than embalmed. This isn’t nostalgia; it’s voltage.

What makes Smug Brothers matter — especially now — is their commitment to the album as an artifact and as an attitude that reflects the music within. The front cover, “Solutions Vary With Regions.” The back cover, “The Hungry Rainmaker” (Artwork by PHOTOMACH. Layout by Joe Patterson and PHOTOMACH). These aren’t afterthoughts; they’re part of the argument. In an era where music is often stripped of context and shuffled into algorithmic soup, Smug Brothers insist on the tactile, the visual, the deliberate. Even when the songs are streaming in invisible code, they carry the residue of collage and ink.

And then there are the songs themselves — all written by Kyle Melton. That authorship matters. Across two decades, Melton has built a body of work that feels diaristic without being self-indulgent. The hooks sneak up on you. The choruses don’t explode so much as insist. The guitars jangle, scrape, shimmer. The drums propel rather than pummel. You find yourself humming along before you realize you’ve been converted.

A retrospective like Gravity Is Just A Way To Fall lives or dies by sequencing, and Smug Brothers have always understood that an album isn’t just a container — it’s a mood swing you consent to. These thirteen tracks trace the band’s restless melodic intelligence, moving from punchy immediacy to sly introspection without ever losing that basement-show voltage. It opens with “Let Me Know When It’s Yes,” a title that feels like a thesis statement for the entire catalog — yearning wrapped in defiance. And to be fair, a song that we have often played on YTAA. The guitars chime with that familiar Midwestern shimmer, but there’s an undercurrent of impatience here, a sense that indecision is the real antagonist. It’s a perfect curtain-raiser: concise, hook-forward, emotionally ambivalent in the best way.

“Interior Magnets” (clocking in at an impressively tight 3:01) is classic Smug Brothers compression — all tension and release packed into a pop-song frame. The rhythm section locks in with that loose-tight chemistry Kyle Melton and Don Thrasher have refined over the years, while the melody spirals inward. It’s a song about attraction and repulsion, about the invisible forces that keep people circling each other. One of our favorite Smug Brothers’ songs, “Meet A Changing World,” expands the lens. There’s something almost anthemic about it — not stadium-anthemic, but neighborhood-anthemic. The guitars layer into a bright, bracing wash, as if the band is daring uncertainty to make the first move. In contrast, “It Was Hard To Be A Team Last Night” — a simply brilliant tune — pulls the focus back to the micro-level of human friction. It’s wry, a little bruised, propelled by a riff that sounds like it’s arguing with itself.

“Beethoven Tonight” is pure Smug Brothers mischief — high culture dragged through a fuzz pedal. The song plays with grandeur without surrendering to it, balancing a classical wink with garage-rock muscle. Then comes “Hang Up,” lean and kinetic, built around the kind of chorus that arrives before you’ve fully processed the verse. It’s sharp, unsentimental, and irresistibly replayable. “Javelina Nowhere” may be the record’s most evocative left turn. The title alone suggests a desert hallucination, and the arrangement follows through a slightly off-center, textural, humming with atmosphere. “Take It Out On Me” snaps the focus back into a tight melodic frame, pairing vulnerability with propulsion. It’s accusatory and generous at once, a hallmark of Melton’s songwriting.

“Silent Velvet” glides toward you, in contrast, with a softness in the title, grit in the execution. There’s a dream-pop shimmer brushing against serrated guitar lines. “Seemed Like You To Me” feels like an old photograph discovered in a jacket pocket: reflective, warm, edged with ambiguity. Late-album highlights “Pablo Icarus” and “Every One Is Really Five” showcase the band’s love of conceptual wordplay. The former fuses myth and modernity, soaring melodically before tilting toward the sun. The latter is rhythmically insistent, almost mathy in its phrasing, but anchored by a chorus that keeps it human.

Closing track “How Different We Are” is less a statement of division than an acknowledgment of complexity. The guitars don’t explode; they bloom. The rhythm section doesn’t crash; it carries. As finales go, it’s quietly expansive — a reminder that across twenty years, Smug Brothers have thrived on tension: between polish and rawness, intimacy and noise, gravity and lift.

If last year’s Stuck on Beta (2025) suggested a band still hungry, still refining, still pushing outward, this retrospective confirms the long arc. Smug Brothers didn’t burn out. They didn’t calcify. They kept writing, recording, releasing, playing shows, and deepening their chemistry. Gravity, in their hands, isn’t a force that pins you down; it’s the thing you learn to fall through with style.

There’s something profoundly Midwestern about that ethos. No grand manifestos. No self-mythologizing. Just songs that are stacked one after another, each carrying its own small revelation. In a culture obsessed with the new thing, retrospectives can feel like retirement parties. But Gravity Is Just A Way To Fall plays more like a dispatch from a band still in motion.

Twenty years in, Smug Brothers remind us that indie rock isn’t a genre so much as a practice: keep the overhead low, keep the guitars loud, keep the songs sharp, keep the faith. The noise may be louder than ever, the platforms more crowded, the attention spans shorter. But when a riff locks in, when a chorus lifts, when a drumbeat nudges your pulse into alignment, none of that matters.

Gravity is just a way to fall. And sometimes, falling is how you learn what’s been holding you up all along.