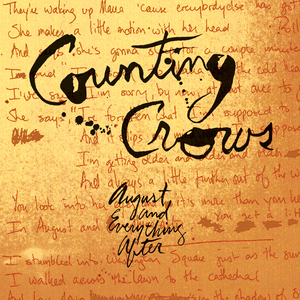

How often have you been asked to name your top ten albums, or debated which records you’d take to a desert island? The “desert island album” is a familiar, hypothetical concept among music fans: the one record you could listen to endlessly and never tire of. It’s simply a way of naming your most cherished, all-time favorite album. For Dr. J, one of those perfect records is Counting Crows’ 1993 debut, August and Everything After.

Some records arrive like polite guests, shaking hands with the radio, smiling for the cameras, making sure not to spill anything on the carpet. And then some records kick in the door at 3 a.m., overwhelmed on their own feelings, bleeding a little, asking you if you’ve ever actually lived or if you’ve just been killing time until something breaks your heart. August and Everything After is the latter. It doesn’t so much introduce Counting Crows as it announces them, like a cracked-voiced preacher stumbling into town with a suitcase full of secrets and a head full of weather. That it’s their first record feels almost obscene. Bands aren’t supposed to sound this fully formed, this bruised, this emotionally articulate right out of the gate. This is supposed to take years of failure, challenges, and ill-advised love affairs. But here it is, fully alive, staring you down.

If genius means anything in rock and roll—and it does, despite all the sneering irony we’re trained to wear like armor—it means the ability to translate private confusion into public communion. Adam Duritz doesn’t just write songs; he writes confessions that somehow feel like yours, even when you’ve never lived in California, never stood on a street corner at night wondering who you were supposed to be, never tried to make sense of love after it’s already gone feral and bitten you. These songs don’t explain feelings; they inhabit them. They sit in the mess. They let the awkward silences linger. They don’t clean up after themselves. And that’s why people keep coming back.

“Round Here” opens the album not with a bang but with a question mark. It’s a song about dislocation, about being young enough to believe that identity is something you can find if you just look hard enough, and old enough to know that it might already be slipping away. “She says she’s tired of life, she must be tired of something,” Duritz sings, and it’s not melodrama—it’s reportage. He’s documenting the emotional static of a generation that grew up on promises it didn’t quite believe. There’s no manifesto here, no slogans. Just the sound of someone pacing around a parking lot trying to figure out how to be real in a world that feels increasingly wrong and staged.

And that’s the trick of August and Everything After: it sounds intimate without being precious, expansive without being bombastic. The band plays like they’re backing a nervous breakdown that somehow learned how to swing. The guitars shimmer and sigh; the rhythm section keeps things grounded, like a friend who knows when to let you rant and when to hand you a glass of water. T Bone Burnett’s production (Burnett also contributed guitar and vocals to the record) gives everything room to breathe, which is crucial because these songs need the oxygen. Smother them, and they’d collapse into self-pity. Instead, they hover in that dangerous space between vulnerability and confidence, where the best rock records live.

“Omaha” — one of my favorite songs on the record — is where the album first threatens to explode. It’s restless, jittery, propelled by a sense that staying still is a kind of death. Duritz sounds like someone running not toward something but away from the version of himself he’s afraid to become. This is a recurring theme throughout the record: movement as salvation, travel as therapy, geography as a stand-in for emotional states. Cities become characters, roads become metaphors, and every mile marker is another chance to start over, or at least pretend you can.

Then there’s “Mr. Jones,” the song that doomed the band to a lifetime of misunderstanding by becoming a hit. People heard it as an anthem of ambition, a singalong about wanting to be famous, to be seen. But listen closer, and it’s a song about emptiness, about mistaking visibility for connection. “We all want to be big stars,” Duritz sings, and it’s not triumph—it’s confession. The song pulses with the anxiety of someone who knows that being watched isn’t the same as being known. That radio stations turned it into a party song is almost beside the point; the genius is that it works despite the misreading, smuggling existential dread onto pop playlists like contraband.

The middle stretch of the album is where August and Everything After really earns its indispensability. “Perfect Blue Buildings” and “Anna Begins” slow things down, letting the emotional weight settle in your chest. These are songs about relationships not as fairy tales but as negotiations, as ongoing attempts to be less alone without losing yourself entirely. “Anna Begins” in particular feels like eavesdropping on someone thinking out loud, trying to talk himself into love and out of fear at the same time. It’s hesitant, messy, human. The song doesn’t resolve so much as it exhales, which is exactly right. Love rarely comes with neat conclusions. And remember, this is the band’s first record — wow.

What makes this record one that everyone has either owned, borrowed, stolen, or at least absorbed through cultural osmosis is how unapologetically it centers feeling in an era that was increasingly suspicious of it. The early ’90s had irony for days. Grunge made disaffection fashionable; alternative radio thrived on detachment. Counting Crows, meanwhile, walked in waving their emotions like a white flag and dared you to flinch. They didn’t hide behind distortion or sarcasm. They sang about longing, loneliness, and the aching desire to matter. And people listened because, beneath all the posturing, that’s what everyone was dealing with anyway.

“Time and Time Again” and “Rain King” push the album toward something almost mythic. Duritz begins to sound less like a diarist and more like a prophet with stage fright, evoking imagery that feels both biblical and personal at the same time. “Rain King” is particularly a masterclass in building atmosphere. It swells and recedes, gathering momentum until it feels like the sky might actually open up. It’s about control and surrender, about wanting to command the elements of your life while knowing that you’re mostly at their mercy. It’s the sound of someone learning to live with uncertainty rather than trying to conquer it.

And then there’s “A Murder of One,” the closer that doesn’t tie things up so much as leave them humming in your bloodstream. It’s expansive, reflective, tinged with regret but not crushed by it. Ending the album here feels intentional: after all the searching, all the restless motion, the record concludes not with answers but with a kind of hard-won acceptance. Life is complicated. Love is risky. Identity is a moving target. The best you can do is keep singing, keep reaching out, keep trying to make sense of the mess.

What’s staggering is that this is a debut. Not a tentative first step, not a collection of demos dressed up for release, but a fully realized statement of purpose. Counting Crows sound like a band that already knows who they are, even as their songs wrestle with uncertainty. That tension—between confidence and doubt, polish and rawness—is what gives August and Everything After its staying power. It feels lived-in, like these songs existed long before they were recorded, waiting for the right moment to surface.

In the end, the genius of August and Everything After isn’t just in its songwriting or performances, though both are exceptional. It’s in its insistence that emotional honesty is a form of rebellion. That talking about loneliness, about the hunger for connection, about the struggle to define yourself in a world that keeps changing the rules—that all of this matters. This is a record that people return to at different stages of their lives and hear something new each time, because it grows with you. Or maybe it just reminds you of who you were when you first heard it, and who you thought you might become.

Either way, it’s indispensable. Not because it tells you what to feel, but because it reminds you that feeling deeply is still possible. And for a debut album to pull that off—to make itself a permanent fixture in the emotional furniture of rock and roll—that’s not just impressive. That’s a small miracle, wrapped in August light and delivered just in time.