When the helicopters circle low over a neighborhood, they make a sound that feels older than electricity. It is the thrum of authority announcing itself. In Minneapolis last winter, that sound mixed with others: the clatter of hurried suitcases, the click of phones spreading warnings in Spanish, Somali, Hmong, and English, the uneasy quiet of schoolrooms where too many desks sat empty. Federal immigration enforcement swept through the Twin Cities with a force that startled even communities accustomed to living with uncertainty.

And, as has happened so many times before in American history, musicians began turning the noise into music.

Protest songs rarely arrive as tidy manifestos. They appear instead as fragments of feeling—ballads scribbled on tour buses, verses tested at benefit shows, choruses sung in church basements and union halls. Bruce Springsteen has spent half a century mastering this art: the ability to take a specific injustice and fold it into the larger story of who we are. His recent live sets have revived “The Ghost of Tom Joad” and “American Skin (41 Shots),” reframing them for a new era in which questions of policing, borders, and belonging are once again painfully urgent. When he introduces those songs now, he often speaks directly about families living in fear of raids, making the connection between past struggles and present ones impossible to miss.

Springsteen has also used newer material to gesture toward the same terrain. In “Rainmaker,” from 2020’s Letter to You, he warns of leaders who “steal your dreams and kill your prayers,” a lyric that fans have increasingly heard as an indictment of the politics that enable harsh immigration crackdowns. At concerts in the Midwest, he has dedicated “Long Walk Home” to immigrant communities, turning an older song about alienation into a present-day pledge of solidarity. The message is classic Springsteen: America belongs to those who build it, not merely to those who police it.

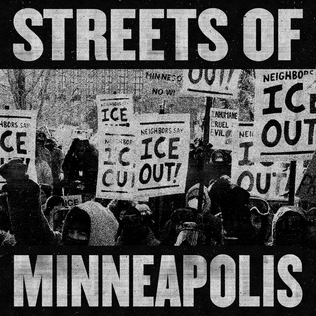

Bruce Springsteen’s “Streets of Minneapolis” stands as one of the most direct and urgent protest songs of his long career, written and released in January 2026 in response to violent federal immigration enforcement actions in Minneapolis. The song’s lyrics paint a stark picture of a city under duress—“a city aflame fought fire and ice ’neath an occupier’s boots”—and explicitly name the deaths of Alex Pretti and Renée Good at the hands of ICE agents as catalysts for the track’s creation. Springsteen recorded the song within days of the events and dedicated it to “the people of Minneapolis, our innocent immigrant neighbors,” underscoring its solidarity with those resisting what he called “state terror.” Musically, it begins with a spare acoustic arrangement before building into a fuller folk-rock chorus that includes a chant of “ICE out of Minneapolis,” transforming the narrative from lament to communal call to action. By invoking local streets and specific victims, Springsteen shifts from abstract critique to vivid storytelling, grounding national debates over immigration enforcement in the lived experiences of a particular place and its people.

Across the Atlantic, Billy Bragg has been sharpening his own brand of melodic concern. Bragg’s music has always insisted that politics is not an abstract debate but a lived experience. In recent years, he has circulated new compositions such as “The Sleep of Reason” and “King Tide and the Sunny Day Flood,” songs that connect nationalism, xenophobia, and state power in plainspoken language.

Billy Bragg’s recent song “City of Heroes” exemplifies how veteran protest singers are responding in real time to state violence and grassroots resistance. Written, recorded, and released in less than 24 hours in late January 2026, the track was inspired by the killing of Alex Pretti and the earlier death of Renée Good—both widely reported incidents involving U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Bragg frames the song around a powerful invocation of Martin Niemöller’s famous warning about silence in the face of oppression, repurposing its structure to insist that individuals must stand up when “they came for the immigrants… refugees… five-year-olds… to my neighborhood.”

Rather than dwelling solely on the perpetrators of violence, the song centers the courage of ordinary Minneapolis residents who “will protect our home” despite tear gas, pepper spray, and intimidation, making the city itself a locus of collective heroism and moral witness. Through its stark lyrics and urgent folk-punk delivery, “City of Heroes” both honors local resistance and challenges listeners everywhere to confront injustice rather than look away.

What is different now is how quickly these songs travel and how intimately they are connected to specific communities. In Minnesota, local artists have woven themselves into the fabric of resistance. Somali American rapper Dua Saleh’s “body cast,” though not written solely about immigration, captures the claustrophobia of living under constant surveillance. Minneapolis songwriter Chastity Brown released “Back Seat” after volunteering with local advocacy groups; the song tells of a mother trying to explain to her son why “men in badges came before the sun.” Musicians have often turned their songs into anthems at rallies.

Nationally, a wave of artists has confronted immigration enforcement head-on. The Drive-By Truckers’ blistering “Babies in Cages” remains one of the clearest condemnations of family separation ever recorded, and the band has revived it repeatedly as raids intensify. Margo Price has performed the song at fundraisers, adding her own spoken-word verses about rural Midwestern towns emptied by deportations. Latin pop star Residente’s “This Is Not America” links border policy to a longer history of hemispheric violence, while Mexican-American band Las Cafeteras’ recent single “If I Was President” imagines a world where “no kid sleeps in a holding cell.”

Music becomes a form of accompaniment. It says to frightened families: you are not alone in this story.

Music critic Ann Powers has often observed that songs do not replace policy. They cannot halt a raid or change a law. But they shape the emotional climate in which those laws are debated. They help define what cruelty feels like and what compassion sounds like. In moments of crisis, they keep the human stakes visible. The current wave of immigration enforcement has produced images that feel almost medieval: agents in tactical gear arriving at dawn, children escorted past news cameras, workplaces emptied in minutes. Musicians respond by insisting on the modernity—and the intimacy—of these events.

These acts may seem small, but protest music has always worked through accumulation. One song becomes a hundred, then a thousand. The civil-rights anthems of the 1960s did not end segregation on their own, yet they provided the soundtrack that made the movement recognizable to itself. Today’s musicians are doing similar cultural labor, stitching together a sense of shared purpose across neighborhoods and genres. There is also a new bluntness in the language. Where earlier generations sometimes relied on metaphor, many contemporary artists name ICE directly. Punk bands from Duluth to Des Moines sell T-shirts that list hotline numbers on the back. Choirs gather outside detention centers to sing lullabies in many languages, turning public space into an improvised concert hall of solidarity.

Still, the best songs resist becoming mere slogans. Springsteen’s gift has always been his ability to locate the political inside the personal: the worker who just wants to get home, the teenager who dreams of a wider world, the immigrant who believes the promises printed on postcards. Bragg, too, mixes anger with tenderness, pairing sharp choruses with melodies that invite sing-alongs. Protest music must be welcoming as well as confrontational; it has to create a community big enough to hold grief and hope at the same time.

In Minneapolis and beyond, that community is gathering wherever music is made. At a recent benefit concert on the West Bank, performers from Somali jazz groups, Hmong folk ensembles, and indie-rock bands passed a guitar from hand to hand while families shared homemade food. Between songs, organizers explained how to donate to emergency housing funds and accompany neighbors to court hearings. The event felt less like a show than a temporary village, built out of rhythm and resolve.

This is how culture pushes back against fear. Not with grand gestures, but with steady, persistent acts of care. A chorus sung together. A lyric that tells the truth. A melody that refuses to look away.

The helicopters will eventually move on. Policies will change, as they always do. What remains are the stories people tell about how they treated one another when the pressure was on. Musicians like Springsteen and Bragg—and the countless local artists standing beside them—understand that their job is to help write those stories in sound: to give courage a tune that can be carried home and passed along.

Somewhere tonight in Minnesota, a teenager is learning three guitar chords and trying to fit the chaos around them into a song. That, too, is part of the resistance. In the long American argument over who belongs, music keeps insisting on an answer both simple and radical: everyone who can sing along.